Boom and Bust in Shanghai's Bike Economy

Gripping the black plastic handle bars and gazing into the vast skyline, Shanghai looked like a city straight out of a mad man’s unrestrained imagination — conceived without regard for the laws of physics or gravity, then scribbled excitedly onto a piece of scrap paper and breathed into reality, buzzing and throbbing with life.

Raman Mama Photography

On my bike, I weaved in and out of the city’s intimate and hidden enclaves, like blood coursing through the veins of a sprinter. If New York was a concrete jungle, then Shanghai was an Amazon — daunting in size, filled with infinite possibilities.

In the 5 months that I lived in Shanghai, biking remedied not only my incessant thirst for adventure, but also the loneliness that being a foreigner in such an immense city had sewn into me. Being lonely in Shanghai was different. In this city of 24 million people, I couldn’t read or understand any of what was being communicated. On my first night at a hostel near East Nanjing Road, I had Oreos for dinner; I was so afraid of getting lost that I counted the number of signs I passed while I searched for something to quiet my grumbling stomach. My thirst for adventure was the same way — I wanted to find something that allowed me to interact with the city, so I could feel like less of a ghostly bystander.

Through word of mouth, I’d heard about Ofo, a start up company that created a phone app which let users unlock one of thousands of yellow “Ofo” bicycles that littered the city. Ecstatic, I downloaded the app and was off on my first adventure.

Bikes allowed my friends and me to experience the intimacies of Shanghai on a whim. With swift pedals of the legs, Wujiachong became Wuchan Road; busy students with backpacks suddenly replaced by young adults enjoying exotic teas in bustling cafes.

The city flowed on like this, shape shifting into infinite communities.

Raman Mama Photography

Monghshan 50 Art District was a sprawling locality bursting with industrial buildings where artists like Ai Weiwei had inspired a contemporary art movement.

The French concession was the home of extravagant manors, commissioned by Western European diplomats who flocked to the neighborhood in the early 20th century.

When a café or artisans shop caught my eye, I’d hop off my bike and wander in.

Though the Shanghai metro would close by 11 pm, the megalopolis resisted a premature repose. With the rented bikes, we experienced the immense city by night. Food sellers on streets would shout “Chǎofàn!” at the tops of their lungs. Vendors selling cheaply made tobacco cigarettes would offer them, as well as a chance to practice our market Chinese. “Wǒ yào yīgè.”. Men sat on stools in front of storefronts, drinking Tsing Tao beer, and playing cards.

If I hadn’t started biking in Shanghai, I might have never made it past my initial conceptions of what I thought the city was — skylines that contained multinational banks and corporations that funneled absurd amounts of money into the linen pockets of wealthy businessmen; factories that churned out goods to be sold in distant corners of the earth; schools that educated some of the world’s most intelligent people.

Raman Mama Photography

After I left Shanghai, my heart ached for it and all of its complexities. When the perfect opportunity presented itself, I bought tickets and returned for a week. When I landed, one of the first things I wanted to do was bike. I plopped my bags in the hostel after my 17 hours of travel and took to the streets. But, there wasn’t a single bike in sight. The streets, once abundant with two wheeled adventure machines, were now completely void of them.

Raman Mama Photography

Every few blocks, I would see a broken bike, missing a seat, stripped of breaks, missing a wheel — but I never found one that was ready to fly.

I asked around to foreigners who I thought spoke English, “Hey, what happened to all of those bikes that used to be around here?” I soon had an answer.

In the months after I left, companies picked up on the sense of adventure that I, and many others had. Some 500 similar companies entered the market, choking the streets with bicycles.

At their peak, there were 1.6 million bikes in Shanghai.

Riders would rent bikes and explore the city, just like I had. However, there were so many bikes that people would leave them in obscure locations. I saw photos of bikes abandoned on the sides of roads, forgotten in bike lanes, and sitting in piles at parks.

Reuters

Companies continued to pump bikes out into the city — I imagine they appealed to the senses they’d stimulated in me. “Come with me and you’ll feel like you own the city”, the bikes said. Soon, so many people felt like they owned the city that the roads were no longer navigable.

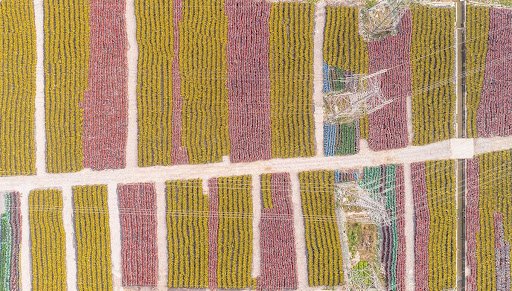

Reading up on the debacle that had transpired since I left, I found coverage with aerial footage of “bike graveyards”, masses of metal, color coded by the different bikes from various companies. Blues and yellows and greens and purples all signalled the excess that swallowed the city.

Shutterstock

For the safety of the people, the government began cracking down on the bike companies, whose supply far outpaced demand. Crews were sent to pick up the bikes and dispose of them.

Evidently, these bike graveyards weren’t unique to Shanghai. They were in Hefei, Beijing, Hangzhou, and many other cities.

During the week I was back, I took the metro. I felt handicapped being confined to it, much less capable of darting around hidden corners of the city as I once had.

Biking around Shanghai showed me that like any city, people here strived and loved and longed and dreamed. Two wheels that I would rent for half an hour at a time gave me access to places that I began to feel like home; the hookah lounge where students huddled on weeknights, the comedy club located in the back of a bar where I began to perform on open mics, and countless other intimate spots.

In the recesses of my memory, biking turned Shanghai into something dynamic and shifting, rather than cold and concrete. In a city of ten million people, I saw that each and every one of them had a soul.